Maybe the Real Horrors Were the Books We Banned Along the Way

Maybe the Real Horrors Were the Books We Banned Along the Way

How books are still being challenged--sometimes successfully--in schools and public libraries in the year 2021, and why that should really alarm you.

Story time:

I grew up very lucky. I’ve always had the love and support of both of my parents, and while we didn’t have a ton of money, I never felt like I had to go without anything. I was also extremely introverted and very much online, so I didn’t actually use the public library much--I used the school library, though, and it still amazes me how it never occurred to me that I would become a librarian until I kind of fell into it by accident.

I was a volunteer at my school’s library during my sophomore and junior year, and the school librarians were...interesting. The head librarian was a sweet but very conservative woman, and she had a slightly younger and slightly less conservative assistant librarian--think a grandmother who insists she loves you but expects you to grow out of being “that way” any day now and a perpetually single aunt who has internalized some of Grandma’s attitude but also wants you to be able to live life the way she couldn’t.

I remember one day when, while Grandma Librarian was gone, Aunt Librarian called me over while we were shelving and showed me a couple of titles I hadn’t seen. “They were in the back office,” she said, quietly slipping them into place on the shelves. “She didn’t feel they were appropriate.”

I asked her why. I remember her hesitating for a moment before shrugging and saying, “Depends on the book. Sometimes if there are curse words, or if there’s adult content, or, you know, if some of the characters are gay, she has me pull them from the shelf.” She wasn’t looking at me, but she leaned slightly closer before saying, a little conspiratorially, “And then when it’s been long enough that I think she’s forgotten about it, I wait until she’s gone and I go put them back where they belong.”

I remember being unable to keep the delighted look off my face, because ooooooh, Aunt Librarian was sneaky! She laughed at my massive grin before pulling me over to the desk.

“It’s just,” she started, then paused. “I remember one time a few years ago, there was a student who came in. She wasn’t here for very long, and when she came to check out, she had a fiction book--I don’t remember the title of that one--and then one book we had as part of a like, tough issue series? But the book was on,” she glanced around and lowered her voice, “incest.”

She paused here, looking at my face, I guess to make sure I was following, or just to gauge how I was reacting so far. Whatever she saw, she nodded and continued. “She didn’t say anything to me, and I didn’t ask. She didn’t look me in the eye once the whole time. And, you know, maybe she was working on a project for a class, or a paper or something.”

Another pause. Her mouth twisted a bit, and then went flat. “But maybe not.”

I remember we were both quiet for a moment, then she looked back at me. “I mean, I didn’t know, you know? I wasn’t going to ask - I couldn’t. And... even if I did ask, and even if there was a good reason for me to ask, I don’t know that she would have told me anything. And even if she had, I have no idea what I would have said. The point is, like...maybe she didn’t need that book for a project. Maybe she just needed it. Maybe she needed to know something.”

“Right,” I said, because this was a lot for fifteen-year-old me at 9:30 in the morning.

“I guess what I’m trying to say is,” she said, sighing. “It’s not for me to say what you kids should and shouldn’t be allowed to see or allowed to know. And I don’t ever want to be the one to keep things from you that you need.”

No other interaction with a librarian has stuck with me like that one did, because that was like, the first real example of the back-and-forth regarding intellectual freedom in libraries that so many people fight about. I have no doubt that Grandma Librarian thought she was doing the right thing, but that’s not what libraries are - not school libraries, and certainly not public libraries.

That message doesn’t seem to compute for many citizens and politicians here in the United States, whose demands for the removal of books they deem “inappropriate” in some regard or another have been escalating. There have pretty much always been book challenges, of course, but it seems like in the last few years, these calls for mass removal and the follow-up calls for the dismissal of the librarians and school officials providing the books have been turned up to eleven.

What’s worse is that, in some cases, it really seems to be working.

It makes sense, though, if you think about it - this is a time of political unrest, misinformation, and, in the middle of it all, a massive public health crisis. What more could you want for a hotbed of paranoia and fear, and what better guise could it have than Old Reliable, “Won’t Someone Please Think of the Children?”

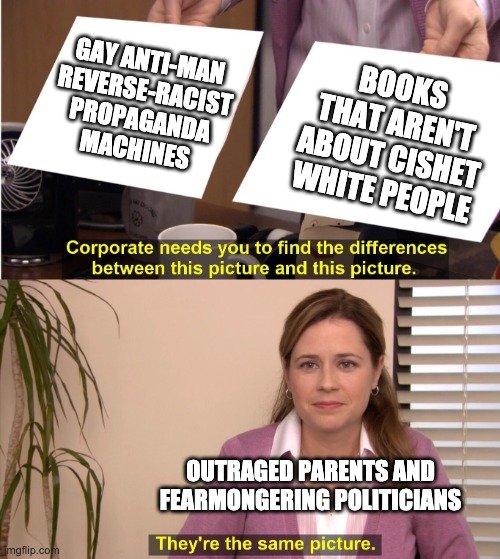

It’s no coincidence that the majority of books challenged in the United States, especially in recent years, are books geared toward children, middle-graders, and teens that contain LGBTQ+ content, explorations of systemic racism and police brutality, and/or rape, sexual assault, and harassment. Anything having to do with sex is going to be met with parental upset and accusations of encouraging inappropriate behavior - the fact that teens already can, will, and do have sex (and have done so since basically the beginning of time regardless of books they read) notwithstanding.

What the actual complaints often entail, though, is more insidious than your average pearl-clutching. For instance, Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak is a 1999 novel about a young teen girl who is raped at a party and, after her call to the police to report the incident ends up getting the party busted, is subsequently ostracized and bullied, even by her friends. The rape itself isn’t depicted in a way that I would call very graphic; what is infinitely more impactful is the deftness with which the author depicts the protagonist’s emotional state and trauma. One of the recent challenges, though, was made on the grounds that not only was its depiction of rape seen as inappropriate for its age group (which is a whole other thing to try to unpack), but also that it was biased against boys and men.

...Yeah. Just sit with that for a moment.

Another issue is the constant conflation of sexual content and LGBTQ+ content, as well as the insistence that even depicting LGBTQ+ characters, no matter how innocuous the actual content, is inappropriate and, to many, an active attempt at indoctrination. Yes, that is correct: it is the year 2021, and people still think reading books about queer characters can brainwash you into becoming queer yourself.

(I imagine if this was true, then so would be the reverse. So, why didn’t the innumerable romance novels I consumed in my preteen years lock me square into heterosexuality? Truly, a mystery.)

Not only is this view bafflingly inaccurate, but it also sends a very clear message to kids, particularly queer kids, who suddenly find books with LGBTQ+ content pulled from the shelves: “We don’t want you here, either.”

Books that delve into depictions of racism have always had their fair share of challenges, too, but recent years have seen more and more titles discussing the systemic nature of racism in the US, including police brutality, and with those books has come a massive backlash against them. Fellow Mississippian Angie Thomas has come under fire many a time for her debut novel The Hate U Give, as have titles from Jason Reynolds, Nic Stone, and other authors whose works deal realistically and unflinchingly with the reality of people of color in the United States.

And therein lies the problem.

The reality is this: most of these challenges don’t actually come from a concern for children, not really. That element may be there, but looming behind it is the very real and present fear that many people don’t seem to know what to do with, and that fear is being forced to have difficult and uncomfortable conversations with their children. Because if kids read this stuff, they’re going to have thoughts. They’re going to have questions. And for some people, the idea that kids may form their own opinions based on information that adults don’t like is enough of a problem that they would be happy to strip away any and all depictions of tough or “inappropriate” topics available in the library.

It doesn’t matter that life doesn’t work that way. It doesn’t matter that racism is still alive and well in America and is threaded through the fabric of our society. It doesn’t matter that misogyny, discrimination, and rape culture are all present and accounted for, the seeds of which can be planted before kids can even really talk. It doesn’t matter that queer people exist and have the right to do so happily and without fear, whether these people like it or not. All that matters is that they don’t have to deal with it. Because if you ignore something long enough, it’s like it’s not even happening, right?

Which is why as imperfect as we librarians are, and as many of these same problems our field has (and believe me, it does), it is vital that libraries do everything in their power to keep these books on the shelves and to display them without apology. Because for every person frothing at the mouth that Alex Gino’s Melissa or Jerry Craft’s New Kid, there are several young people who are feeling seen and heard by those books, and still others who are learning to empathize with their fellow humans through those books.

Maybe Aunt Librarian’s act of defiance was a small drop in the ocean in terms of comparative impact, especially in a conservative school in a very conservative town in a very conservative state. But I’ve taken that moment with me throughout my entire library career, and it’s something I impart to other librarians all the time. And I like to think - I hope, at least - that it has bigger ripples than she ever thought it would.

Want to see more? Head over to Book Riot for Kelly Jensen’s Anti-Censorship Toolkit, this article from Sarah Nicholas on How to Support Libraries in Times of Increased Censorship, and this list from Lucas Maxwell with 5 Ways You Can Support Your Local Public Library in the UK. You can also check out A Deeper Look: Censorship Beyond Books from Kristin Pekoll on American Libraries Magazine and a rundown of how students in the Central York (PA) school district fought back against a massive removal of books in their schools from Kara Yorio at School Library Journal.

Kayla Martin-Gant (she/her) is a queer disability advocate, full-time librarian, and lover of all things spooky. She wrote her first story, called The Haunted Dollhouse, when she was seven years old and received rave reviews from the playground crew. You can find her yelling about various and sundry things on Twitter at @poultryofperil.