Queer Domesticity & The Pull of the Full Moon

Queer Domesticity & The Pull of the Full Moon:An Exploration of Family Ties in An American Werewolf in London and Good Manners

Trigger Warnings: descriptions of violence and sexual activity

Note: This article may also contain some spoilers for An American Werewolf in London and Good Manners.

A pair of children sit before a thick, rabbit-eared television, Ms. Piggy and Kermit the Frog arguing from afar as two puppets spar in the background. Their father sits nearby on the couch, the sound of him flipping the pages of his newspaper serving as a constant against the noise of the show. Their mother scrubs, scrubs, scrubs at a sink of dishes. A pencil scratches across paper as eldest son David Kessler works on homework at the dining room table.

It’s the noise of a classic American household, unremarkable till there is a knock at the door. The knock itself isn’t even all that remarkable at first. Until it becomes insistent, unrelenting. A pounding that pulls the children’s’ eyes away from their program, that causes the frustrated mother to shout for her husband to get the door. David’s pencil pauses on the page as he watches his father rise, assuring the knocker that he’s coming and to hold their horses. David’s father opens the door, then that American nuclear ambiance is blasted by the sound of gunfire. A group of gun-toting, torch-welding werewolves in uniforms reminiscent of those belonging to Nazi officers force their way into the household, executing the family with violence and setting their American dream ablaze.

An American Werewolf in London tells the story of David Kessler (David Naughton), a recently-graduated college student who is backpacking across England when him and his best friend Jack Goodman (Griffin Dunne) are attacked by a werewolf. While David survives his injuries and finds himself moving in with English nurse Alex Price (Jenny Agutter) after a whirlwind romance, he’s haunted by visions of a dead Jack warning him that should he not kill himself before the full moon, he will transform into a werewolf. The film marks a dramatic shift in director and writer John Landis’ career as the film was his first foray into horror filmmaking, following a string of successful raunchy comedies like National Lampoon’s Animal House and The Blues Brothers. An American Werewolf in London opened to an impressive $60 million run against a $5.6 million budget, persuaded other filmmakers to be less fearful of comedic horror, and even encouraged the Academy of Motion Pictures to create a category to honor makeup following the impressive creature design of special FX make-up artist Rick Baker; however, the film is tonally consistent with Landis’ past works, which were primarily intended for the heterosexual male audience. Despite this, thematically the film explores the constant conflict between the heterosexual domestic relationship between Alex and David and the inevitable pull of the werewolf transformation brought about by the full moon. By considering the subtle queer-coding of Jack and David’s relationship and the association of lycanthropy with sex, we can view the film to be an exploration of how closeted domesticity is constantly undermined by homosexuality, considering the context of Landis’ frat brother-esque approach to filmmaking and the 1982 release of the film.

Upon my first watch of An American Werewolf in London, I was particularly drawn to the film’s iconic poster, which shows David and Jack looking over their shoulders at a wolf-shaped cloud outlining the full moon. What drew me to the poster was the blocking of the characters with Jack’s body positioned between David and the ominous shape, thus serving as foreshadowing that the murder of Jack would be the only thing keeping David from a similar fate before the village people arrive to rescue the pair. While watching the first twenty minutes of the film prior to the werewolf attack, Jack and David’s relationship can be analyzed through a queer lens. Particularly, in David’s doting concern for Jack, continually checking to see if Jack is enjoying himself or if he’s cold or hungry. While these interactions may seem superficial—after all, we as human beings care for our friends and their well-being—it is John Landis’ reason for putting Jack and David backpacking in the English moors and David’s dismissiveness of it that makes me think there’s something there that’s more than a simple friendship. Early on in the film, Jack urges David to not slow down, as it will only delay Jack’s chance at having a sexual rendezvous with an old classmate. While we might expect John Landis to divulge into a conversation about how awesome this prospect is, David is instead dismissive of Jack’s goal, lamenting that his friend is wasting his energy on a dull woman with a good body. The pair argue back and forth with David becoming increasingly irritated at Jack’s efforts. This clear deviation from John Landis’ frat brother humor can be seen as an indication that David’s frustration stems from jealous feelings directed towards Jack, urging his friend to forgo rushing their trip to meet this woman to instead spend more time with David. But David never gets the opportunity to finish his trip with Jack, because their trip is cut short by the gnashing of teeth and mangling of flesh as the full moon draws a werewolf to kill Jack and near fatally injure David.

In the aftermath of this bloody encounter, David finds himself confined to a hospital bed. In a singular scene, David learns that he was attacked by a mad man, and while he survived, his best friend Jack did not. The grief hits David hard in this moment as his denial is immediately undermined by the revelation that Jack’s body has already been returned to America and buried. Having been inhibited by his recovery, David has found himself forced to confront weeks’ worth of emotions in public view as both his doctor and Nurse Alex Price observe him. His emotional response is seen as secondary to his physical recovery, reflecting in a way the sentiments of the 1980s regarding the large physical and emotional toll of the AIDS epidemic. The queer community found itself trapped between the realities of the AIDS virus ravaging their bodies and the homophobic notions held by society and governments across the world that forced them to hold out on acknowledging their identities at the risk of additional repercussions. These conflicting tensions resulted in a generation forced into silence, unable to publicly grieve their communities without further isolating themselves from society and non-LGBTQ loved ones. David finds himself in a similar scenario, unable to properly grieve his friend by being denied the ability to attend Jack’s funeral. David’s feelings, while not entirely dismissed, are considered secondary to his own health. Trapped in a hospital in a foreign country, David is left with nothing but his emotions. Perhaps, due to this isolation, it only makes sense that he’s drawn to Nurse Alex Price, his only human connection beyond the doctor’s methodical approach to his recovery. David’s life post-recovery is a question that is unanswered until he meets Alex, so after a clear romantic connection forms between the two and Alex invites him to come live with her, David jumps at the opportunity.

But while Alex’s love is an effective medicine to aid in David’s recovery, their relationship enters new territory as David leaves the hospital and the month anniversary of David’s attack approaches. The fact that this anniversary coincides with the full moon adds an additional obstacle to their whirlwind romance. An American Werewolf in London takes an interesting approach to establishing David’s eventual transformation. While the scene detailed at the start of this article and another bizarre dream keeps the question of David’s lycanthropy in the audience’s mind, the certainty of David’s transformation with the full moon is juxtaposed by a sex scene between David and Alex. Following the sex scene, David sees a vision of an undead Jack, his body horribly torn apart with the mark of his killer’s claws. Jack explains that due to the nature of his death, he’s trapped in a purgatorial existence, unable to move to the next life until the werewolf’s curse is broken. While David reacts emotionally to seeing his lost friend and this new revelation, Jack’s arrival comes with a demand: that David commit suicide before the full moon. But considering the things that are going right in David’s life, particularly the prospect of sharing a life with Alex, he’s extremely resistant to the prospect of suicide. Jack’s demand comes with a means of forcing David’s hand: David’s dreams are prophetic and if he doesn’t commit suicide before the full moon, David will transform into a werewolf and surely expand the ranks of tortured souls trapped with Jack.

The next night, Jack’s prophetic warning comes true as David’s body grotesquely contorts and transform into a more lupine form. His domestic life with Alex is thrown off-balance as he disappears into the night, a werewolf whose first victims represent everything he wants. That first night, David kills a business man on his way home to his children and a young straight couple seemingly celebrating their engagement with friends. The next day, David arrives home to a concerned Alex who demands to know where he was. Initially, he’s unable to explain his whereabouts, but as the day progresses, David is forced to acknowledge that he is the one responsible for the strange murders committed the night before. Unlike other werewolf mythologies, David’s transformations aren’t entirely tied to the full moon, and his day is colored by the knowledge that he will very well transform later that evening. In a tearful confession to Alex, David says, “Jack was real. He warned me, and I thought I was crazy. I love you, but I think I did some terrible things that I don’t remember. I love you, but I have to be away from you, Alex.”

This moment serves as a crossroads. David has no choice but to accept that regardless of what he wants, he’ll never be able to live the normal life that he imagined. Even if David loves Alex, a life of domestic bliss isn’t one that they can share together. David’s lycanthropy and the pull of the full moon can only end in tragedy, and it is with that finally declaration of love to Alex that David flees into the night. David flees to a porno theater where he’s confronted by visions of Jack and David’s victims, pressuring him to kill himself before the beast expands their ranks; however, it’s too late and soon David is a mad werewolf running through the streets of London. Alex, hearing the news of David’s rampage, runs to where the police have cornered the beast, and in one last act of love, she throws herself between the police and David’s werewolf form, only for a shower of bullets to kill David once and for all. In this case, love isn’t enough to save David.

Looking at An American Werewolf in London as a queer film reflects societal sentiments surrounding queer life and domestic behavior in the 1980s. Particularly, if we view David’s lycanthropy as a metaphor for queerness itself, the film seems to comment that despite David’s love for Alex and his want to achieve domestic bliss with this woman, his transformation with the full-moon will always undermine any happiness the pair find. In much the same way that closeted queer people were forced to pass as straight and maintain the illusion of a happy nuclear family while their homosexuality came in direct conflict with this lifestyle, David is unable to ever achieve true happiness with Alex because there will always be the guilt that in order to maintain his lifestyle, he must accept the risk that he’ll kill during the full moon. An American Werewolf in London, when viewed as a queer film, lacks optimism regarding the possibility of queer domestic happiness, instead postulating that the so-called LGBTQ+ lifestyle was one that was incompatible with society’s idea of domestic relationships.

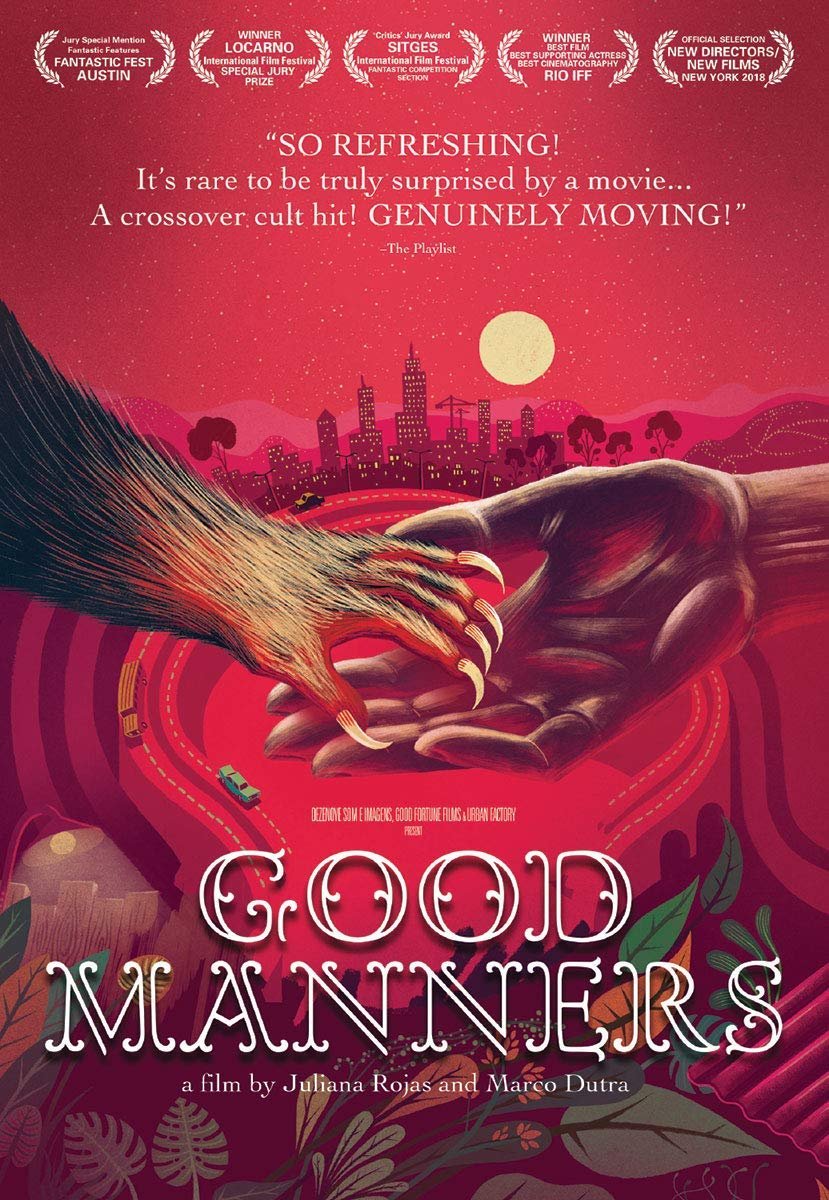

But while lycanthropy and queerness in the 1980s could be viewed as a death sentence, modern werewolf films when analyzed through the same lens do not hold the same pessimism regarding the possibility of a happy, healthy queer household. Particularly, we can view the critically-praised Portuguese werewolf film Good Manners (2017) as a direct counterargument to the queer sentiments and concerns expressed in An American Werewolf in London.

Good Manners tells the story of Clara (Isabél Zuaa), a nurse who finds herself hit by hard times, who agrees to serve as a live-in nanny and housekeeper for the rich Ana (Marjorie Estiano). While Clara’s lack of references and clear apprehension of children initially causes the pregnant Ana to reject her from the position, Clara’s medical experience and caring manner prove her the right person for the job as Ana has a painful pregnancy pang at the tail-end of their interview. After moving in with Ana, Clara is tasked with monitoring the difficult symptoms of Ana’s pregnancy, particularly noticing how Ana remains sick and lethargic, only to display a ravenous craving for meat and sleep-walking with the approach of the full moon.

Clara remains distant from Ana until one night Clara arrives home to find a very pregnant Ana consuming raw meat from the refrigerator. Upon confronting her, Clara is taken aback by Ana’s amorous reaction, seemingly surprised that the straight-passing Ana is attracted to a lesbian like her. But before the embrace can become sexual, Clara is disturbed as Ana bites and attempts to drink Clara’s blood. The violence of this moment convinces Clara that Ana’s affection was just another manifestation of her sleep-walking; however, Clara, having at this point convinced herself that Ana’s affliction is tied to the full moon, approaches her job with a much more personal interest, seeking to aid and comfort Ana through the rest of her pregnancy. Even after she watches Ana tear apart a cat during the next full moon, Clara doesn’t run from Ana, but rather tries to accommodate her, even going as far as to mix her own blood with Ana’s food to alleviate her symptoms.

As the pair grow closer, Ana explains that she’s found herself alone, pregnant and without a husband or family, because she ruined her engagement to a wealthy man after getting pregnant in a one-night-stand with a mysterious stranger who disappeared with the emergence of the full-moon. Then, fully lucid, Ana embraces Clara once again, proving to Clara that their previous encounter was the result of Ana’s love for Clara instead of another symptom of her condition. After deciding Ana’s baby’s name together, it looks as if Ana, Clara, and the unborn baby will be able to live together as a happy family, despite the strangeness of Ana’s condition.

But with the next full-moon, this domestic fantasy is torn apart as Ana goes into labor and is subsequently ripped to shreds as the werewolf infant tears itself free from Ana’s womb. Clara, returning home to find the carnage, decides to kill the child, but upon finding the dead Ana and the scared, though monstrous, baby, is unable to go through with it. The rest of the film deals with Clara raising her and Ana’s son Joel, despite his monthly transformation into a werewolf. Clara raises Joel with caution, locking him away during the full-moon and forcing him to adapt a vegetarian diet to weaken the hold his condition has on him.

Despite Clara’s best efforts, the thing that disrupts the domestic life she’d forged for her and Joel isn’t his lycanthropy, but rather the natural rebelliousness that comes with a child a growing up. When Joel finds evidence that Clara isn’t his real mother, he sneaks away from Clara during the full-moon, resulting in him mauling a classmate and drawing the attention of neighbors and authorities to their household. Clara attempts to flee with Joel, but as a mob encroaches on their home, Clara realizes that they only way for their family to survive is to acknowledge Joel’s condition. In the final moments of the film, Clara releases a transformed Joel. Both mother and son stand up to the society that wishes to hunt them down and destroy their life, even if it means carnage.

In the case of Good Manners, lycanthropy is viewed less as an unsolvable problem, but rather as something that must be accommodated. Clara recognizes that Joel is who he is, werewolf or not. Regardless what he does, Clara as a loving parent, must love, nurture, and protect him. Their domestic life, while non-traditional and far from ideal, is one that isn’t viewed as impossible, but rather complicated. In an era where parents are both publicly criticized and legally antagonized for supporting their children’s sexuality or seeking medical support for gender-affirming care, Good Manners shows that a parent’s love and support can itself be life-saving treatment, if we view lycanthropy in this film as a metaphor for queerness.

As queer people, we are forced to accept that not everyone is going to approve of our lifestyle, nor is everyone who says they support us going to be there to defend us when our rights are attacked. While a movie like Good Manners can’t exactly change the world we live in, I think that such an example of unconditional parental love, especially when layered in so much queer subtext, proves that we no longer exist in a society where queerness completely undermines the possibility of happy queer domesticity. A family like Clara and Joel’s might not be traditional as the one imagined in An American Werewolf in London, but is also one that can survive regardless of the obstacles that lycanthropy poses. Queer people no longer have to accept that being queer is enough to disqualify them from raising a family or living a long healthy life. Our need to live our authentic lives, much like the pull of the full-moon to a lycanthropy-stricken individual, is something we cannot deny, but that doesn’t mean that we can’t reimagine and contort the traditional views of what a family is to create familial units that support, cherish, and allow us as queer people to strive.

Justin Moritz (They/He) is a non-binary writer of queer horror, ranging from grotesque camp to societal filth. Raised on true crime and horror movies from way too young of an age, their work tends to explore the terror of living as a queer person in modern times, while adding a speculative twist. Currently based in Austin, Texas where they're pursuing an MFA in Screenwriting at the University of Texas at Austin, they hope to help expand the types of queer representation seen in horror via prose, screenwriting, and academic writing. They've been featured in Sci-Fi and Scary's Twisted Anatomy body horror anthology and are currently working on writing and producing several queer horror short films. You can follow them on Twitter at @jeepers_justin.