From Hades to The Song of Achilles: Greek Mythology Still Slaps

From Hades to The Song of Achilles: Greek Mythology Still Slaps

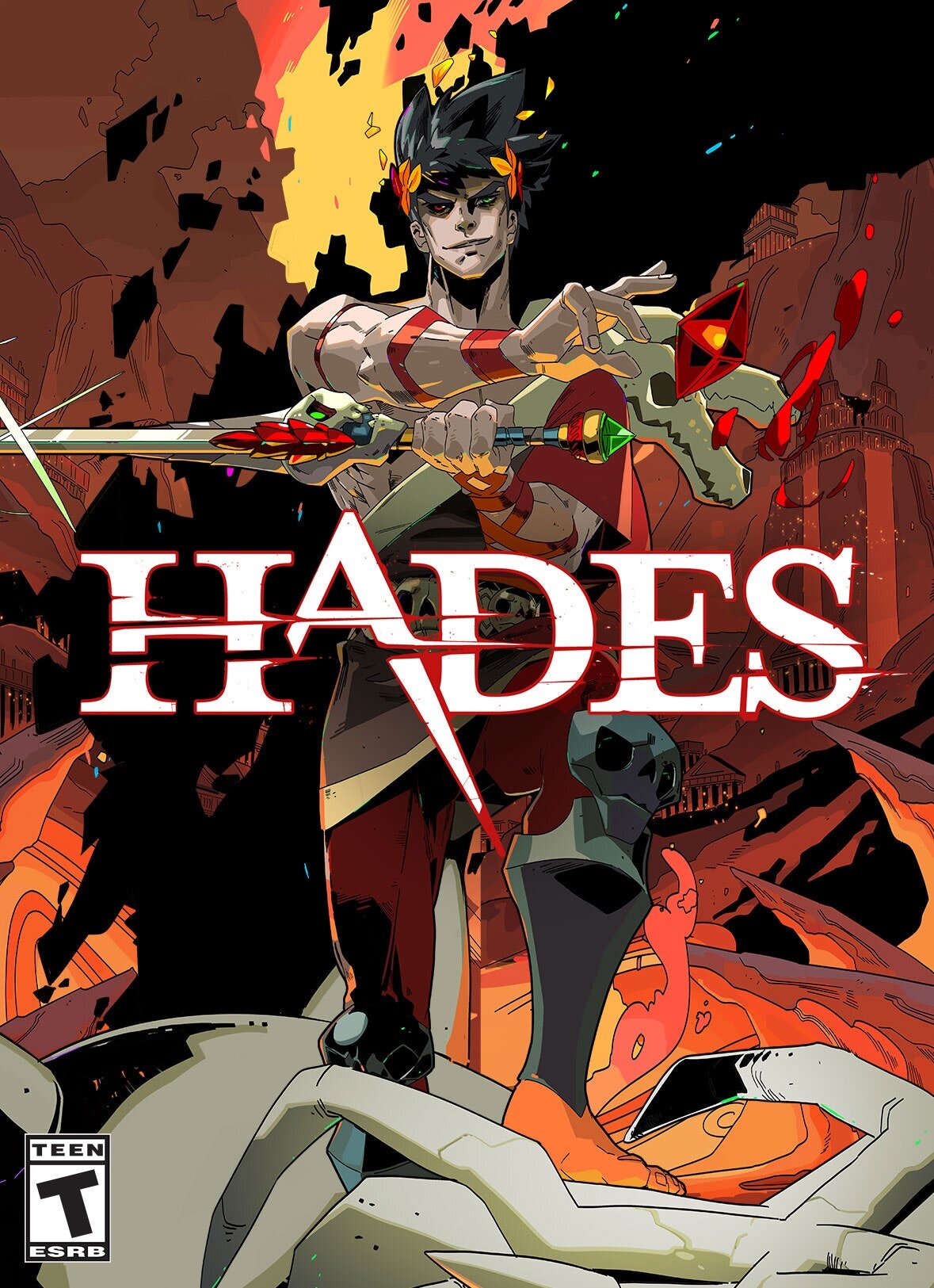

If you’re a very Online individual, you may have noticed some hubbub around the video game Hades over the last couple months. On Thursday, 25 March, the indie light-roguelike Hades took home 5 awards for Game of the Year, Artistic Achievement, Game Design, Narrative, and Best Performer in a Supporting Role (Logan Cunningham). It’s an incredible achievement, but why is it that this little game that could managed to capture the attention of so many across the globe?

That, dear reader, has to do with how fluid the Greek mythos is. When it comes to Hades, the main character is Zagreus. He’s an actual character from Greek mythology, but hardly anything has been written about him. In fact, the game was originally meant to star Theseus as he tries to escape the Labyrinth, but it simply didn’t gel. When the developers found out about Zagreus, though, they had a very open slate with which to build a whole new in-game lore around, leading to the game being Very Gay, Very Sassy, and Very Not-Toxic Masculinity. Death Incarnate is definitely gay, the First of the Furies is a dominatrix who will gladly step on you, Orpheus is a mess and a half, and Theseus has been relegated to Musical Theater Kid/Wrestler Heel standing. Couple that with an incredibly ravenous fanbase, and you got yourself a blockbuster.

I would argue, though, that Hades has merely been the culmination of the past few years of taking back Greek mythology and viewing it through modern eyes. The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller (2011) continues to be a steady seller by placing Achilles’ lover, Patroclus, front and center. Achilles is still one of the great warriors of lore, but by taking away the heteronormative aspects forced upon the legend from translators in centuries past, both men come into their own under her pen. It also adds to something that the modern LGBTQ+ community craves: history and stories that center around others like themselves.

All this is to say that Greek mythos is and always will be open to interpretation. Do you not like the “traditional” telling of The Taking of Persephone? Rachel Smythe didn’t, so she created the webcomic Lore Olympus (2018) which has a fiercely loyal and ever-growing fanbase. How about the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice? We all know it, but what if it’s spun in conjunction with exploring the relationship between Persephone and Hades? Do that, add a sprinkle of the Great Depression and jazz, and you’ll get the 8 Tony Award-winning musical Hadestown, written and composed by Anais Mitchell and directed by Rachel Chavkin.

But going back even further, Millennials can possibly point to Disney’s Hercules as one of the first times they saw the mythos twisted into something more palatable for the modern consumer. They also saw the first few novels of Percy Jackson come out, bringing even more flexibility to the mythos by creating an entire world of demigods navigating the digital age.

Countless novels and series have come out with reimagined mythos, but you’ll find that a great number of them tend to center around Hades and his realm. This is because, like stated above with the videogame Hades, there isn’t as much documentation about the land of the dead. Most likely this is due to the culture collectively fearing death and not wishing to speak about it, but for us today, that empowers us to make the stories fit our needs. In the novel space, we’re also beginning to see a great many stories centered around mythology side-characters. Circe by Madeline Miller (and my rabbit’s namesake, may she turn her enemies into pigs), Ariadne by Jennifer Saint, Sweet Venom by Tera Lynn Childs, and even The Sandman by Neil Gaiman (along with his American Gods novel and series adaptation) have re-envisioned the tales anew.

But where would this article be if I didn’t bring appropriate attention to the magnificent work of the fandom? The very nature of the mythology being up to interpretation has lead to some incredible works. Did you ever think that maybe Dionysus could be a trans man? He was raised partially as a girl in the mythology, so why not imagine him being a trans man god, completely confident in all he says and does. On the other hand, I’ve seen art and fanfiction where the Furies and Athena are all trans women. There is an entire AU where Hermes is a sex worker, and he is very proud of his job and has the support of his half-siblings.

One thing I have noticed with the fandom, though, is very interesting to me. There are very few coming out or coming to terms with gender identity stories. Nearly all of them just...are. No questions asked, next to no homophobia or transphobia. The fans have made their interpretations of the characters reflect an inner confidence and assuredness we all strive for while also molding their realms to reflect a more open and accepting society. That kind of comfort is something I didn’t know I was missing in my life until I started down this fandom path. And that ability to make a comfortable and welcoming space is exactly why Greek mythology continues to slap so hard. Those that love it truly love from the bottom of their hearts, and pour their own ideals and experiences into every piece they send out into the world. And, in my opinion, the world is all the better for it.

By Regi Caldart

Twitter: @IgnatiaStrigha