Hill House and the Manly Hat Problem

Spoiler alert: This Essay contains spoiler details from the series

“The Haunting of Hill House” on Netflix by Mike Flanagan.

Hill House and the Manly Hat Problem

I'm not one to write complimentary things about men. I objectively understand there are some good dudes out there, but I never feel entirely comfortable, even around the best of them. That said, I admit without reservation that I was moved by how Netflix’s “The Haunting of Hill House” uses Luke's story as a vehicle to examine toxic masculinity.

Luke is not inherently a toxic male character. His natural tendency is to be gentle, curious, and he loves his family. He's not perfect, nobody is, and he makes many of the mistakes those among us who suffer with addiction tend to make. In any other show he'd be the archetypal addict and nothing more. In Hill House, nothing is so simple. Luke's character arc is a study of what “being a man” means, and both Julian Hillard and Oliver Jackson-Cohen nail the performance.

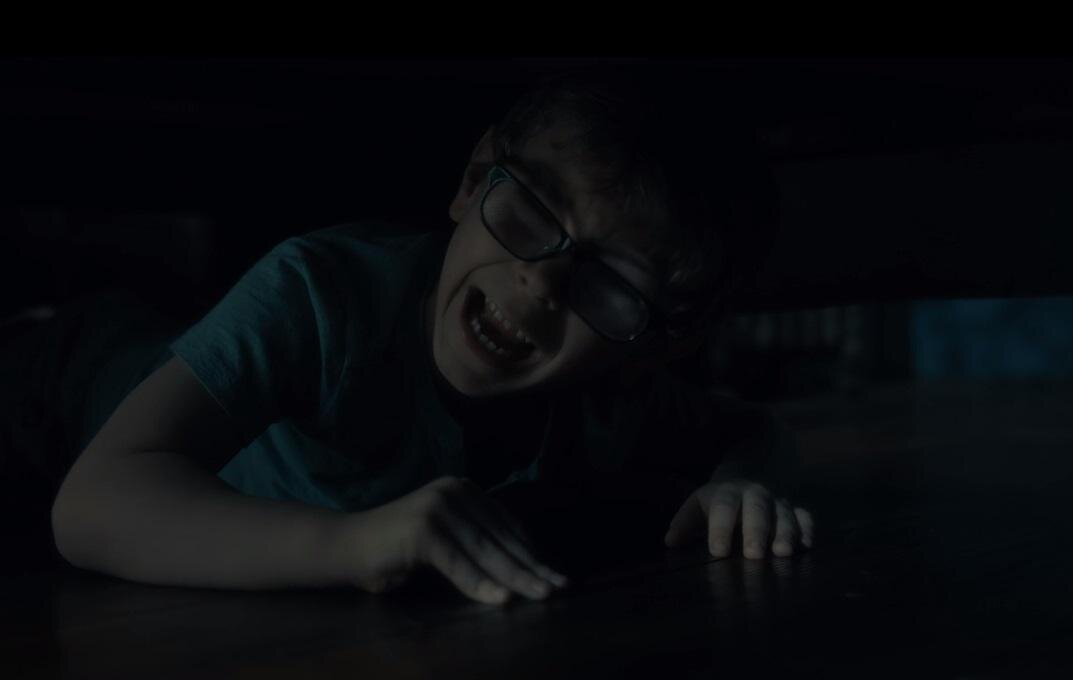

Luke is a very quiet kid. I relate to him so hard. I was that little blonde kid with glasses, afraid to push for my space in any group and trying to figure out where I fit in the world. Luke's interpretation of the red room is a tree house, the kind his father never has time to make (read: never makes time). That room reacts to the desires of the person inside. It's a space of his own, and he tries to prevent people from intruding for that reason.

In the first episode we see that Luke seeks the approval of his older brother, Steve. He asks him for help with spelling, and Steve tells him how to do it. The sign reads “no girls allowed.” I don't think this is intended to be a sexist message, rather that his sister Theo is a strong personality and it seems from the dialogue that she's invaded his personal space before. He just wants a place to hang out with Steve, and pretend that his dad took the time to do something specifically for him (the tree house).

The deepest foundational moment in which we see toxic masculinity being passed onto Luke is when he finds the bowler hat. He's a kid, and he just thinks that the hat looks cool. His dad tells him that it's “a big boy hat”, and that “big boys know the difference between what's real and imaginary.” Trouble is, Luke actually saw something horrifying in the basement. Hugh, the dad, doesn't believe him, and so these words break something precious inside little Luke's mind, and the shards of it are sharp.

He knows what he saw was real. The basement ghost actually tore his shirt. His dad, however, is telling him it didn't happen, and if he wants to be a big boy (if he wants to be a man), he has to accept that it wasn't real. So often kids are taught that being afraid isn't “manly” and discouraged from expressing fear. Too often this is because the nuance needed to approach fear is more than the parent wants to and/or can handle.

Hugh's behavior here is part of the well worn grooves of traditional fatherhood, and it creates a wound that follows Luke for decades. It's like setting caltrops around his self worth, and every time he tries to fulfill some aspect of self worth, something else draws blood. This is how it starts for so many young men, as well as Trans folx. A kid's self worth becomes dependent on “being a man”. The child becomes an adult, all the time trying to uphold that false, toxic notion of masculinity, and ultimately neglects the things that are actually true about them.

Adults who grow up like this tend to center their personalities on things external to them. A habit, a style, a movement. For men and masc-presenting people, a part of this involves holding onto images of masculinity that they've been taught are markers of being a man, an adult, in control. The idea of letting these things go is terrifying, because this false masculinity tends to be there in lieu of emotional development. If they let the image go, all that's left is a scared little kid who wanted to not be afraid or alone.

Let's return to Luke. This little boy goes to bed with the hat, but wakes to the terrifying reality that another ghost is present. The tall man ghost is associated with the bowler hat, the same one that his dad imbued with the meaning of manhood. The ghost wants his hat back. This is a traumatic event in itself, and further reinforces the knowledge that he isn't imagining things.

He wants to grow up, be brave, make his dad proud...but he still sees these things. He's still afraid. This deepens the wound, and solidifies the hat as both a symbol of manhood and as a reminder that there really are ghosts. The two things are opposed, and so how can he ever feel like he's good enough? Everything he does, to his perception, either fails to meet his father's expectations, or stands in opposition to what he knows to be true.

After the events of his childhood in Hill House are over, he is haunted by the ghost of the hat man. That's how it's presented...but I don't think the hat man ever leaves Hill House.

I think the tragedy of Luke's story is that he absolutely saw ghosts in the house, but that he only saw trauma induced hallucinations after he left, until Nell's funeral. Something about the nature and entity of Hill House keeps the ghosts there. It's the same reason that Olivia tells Hugh that he never really saw her until he came back all those years later. What Luke sees as the hat man out in the world is a visual representation of the identity paradox that lives inside his mind.

He doesn't find any peace in this until right near the end of the show, when Olivia is trying to get him to stay with her and Nell in death. She tells him that it wasn't his fault, that the world was hungry and he should never have been fed to it like he was. There's a degree of moral muddiness to this, I know. Perhaps Olivia is just telling him what he needs in order to stay. Even so, it does give him what he needs in order to loosen his grip on that paradox. That lie that haunted him his whole life.

In my ideal world, Luke would be Trans. As a non-binary person, it would've heightened my connection to him, but I don't need it in order to draw the parallels. I've experienced things that are analogous to this. I was never attacked by a ghost (as far as I know), but I was encouraged to be a big boy, and eventually to “act like a man”. I don't get to have a closed loop end to the story though, like a character in a show. Most of us don't. We live with that pain.

For those of us who live with this, watching that moment when you can see him relax his grip on that sharp thing inside is powerful. I watched a few scenes from the last episode again to make sure I was hitting the points I meant to. I'm crying again and it's so worth it. The experience of watching this show and giving in to the feeling of it is just like Nell says forgiveness feels like. Warm, like a tear on a cheek. You're moved, and it hurts, but it's a good hurt, a healing hurt...and the rest is confetti.

Essay by Dan Sexton-Riley

Dan Sexton-Riley is a British transplant living on Cape Cod with their family and a menagerie of small monsters. Dan fills most days with writing, reading, and baking. Their work can be found at Divination Hollow Reviews and Bewildering Stories. Dan also runs a Patreon dedicated to baking tutorials.

Socials are all @dansextonriley

Website is dansextonriley.com

Patreon is patreon.com/dansextonriley