Won’t Somebody Please Think of the Children: How A Modern Moral Panic Has Turned the Library Into A Battle Ground

Almost two years ago, I wrote an article about the increasing number of book bans in the United States. I got a lot of positive feedback and answered a lot of questions from people who hadn’t really understood how bad things were getting. I also got a few folks who told me–some gently, some not–that I was probably being just a bit dramatic.

It brings me absolutely zero joy to tell you that those people were wrong. If anything, I wasn’t being dramatic enough. However, there are still quite a few people who don’t see what the big deal is.

I’ll be happy to explain, but first, a little context will be helpful.

THE WHAT:

What exactly is censorship in the context of library materials? I like to break it down into three easy categories (that all start with R because alliteration is useful):

● Removal. This is first because it’s the most obvious and, typically, what people think of when they hear the term “book ban.” It means that the item in question is either banned from the collection entirely or, as has been happening more and more lately, held back for “review,” sometimes indefinitely.

● Rejection. By this, I mean a librarian’s refusal to order due to personal beliefs or fear of reprimand, either by superiors or the general public. This is sometimes referred to as “soft censorship,” and librarians sometimes engage in this behavior without even realizing it.

● Restriction. Restricting books (or other library materials) means requiring patrons to have certain permission to read, reshelving the materials into a different (usually older) age group, and/or labeling the books according to content.

(“Okay, wait,” you may be saying, “labeling books is bad, now?” It may sound counterintuitive to you–after all, would labels not make it easier for people to find books they’re looking for?

Well, aside from being a logistical nightmare of overlapping genres and unconscious bias, imagine for a moment being a queer teen in a conservative town desperately wanting to read a book that has people like you in it, and being unable to bring yourself to even look at it too closely because it’s got a big rainbow sticker on it.

If you’re like me and don’t have to imagine that because that pretty much describes how you grew up, then you know any visible indicator of queer content might as well be the fucking Bat Signal to bigots.)

THE WHEN:

Some notable dates in the history of US censorship:

● 1650: William Pynchon publishes The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption and Puritan Calvinists get BIG MAD.

● 1851: Harriet Beecher Stowe publishes Uncle Tom’s Cabin about the evils of slavery, which is burned, banned, and cause to put people in prison.

● 1873: Passage of Comstock Act, a law prohibiting the possession or dissemination of “obscene” or “immoral” texts.

● The 1950s bring us McCarthyism and the Red and Lavender scares due to the Cold War, fear of Communism, and more.

● 1969: In Tinker vs. Des Moines, the Supreme Court rules that “neither teachers nor students shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

● The 1980s had Jerry Falwell and the Moral Majority, Reagan, and the AIDS crisis.

● 2021: Formation of Moms for Liberty group and the beginning of their extensive censorship campaign.

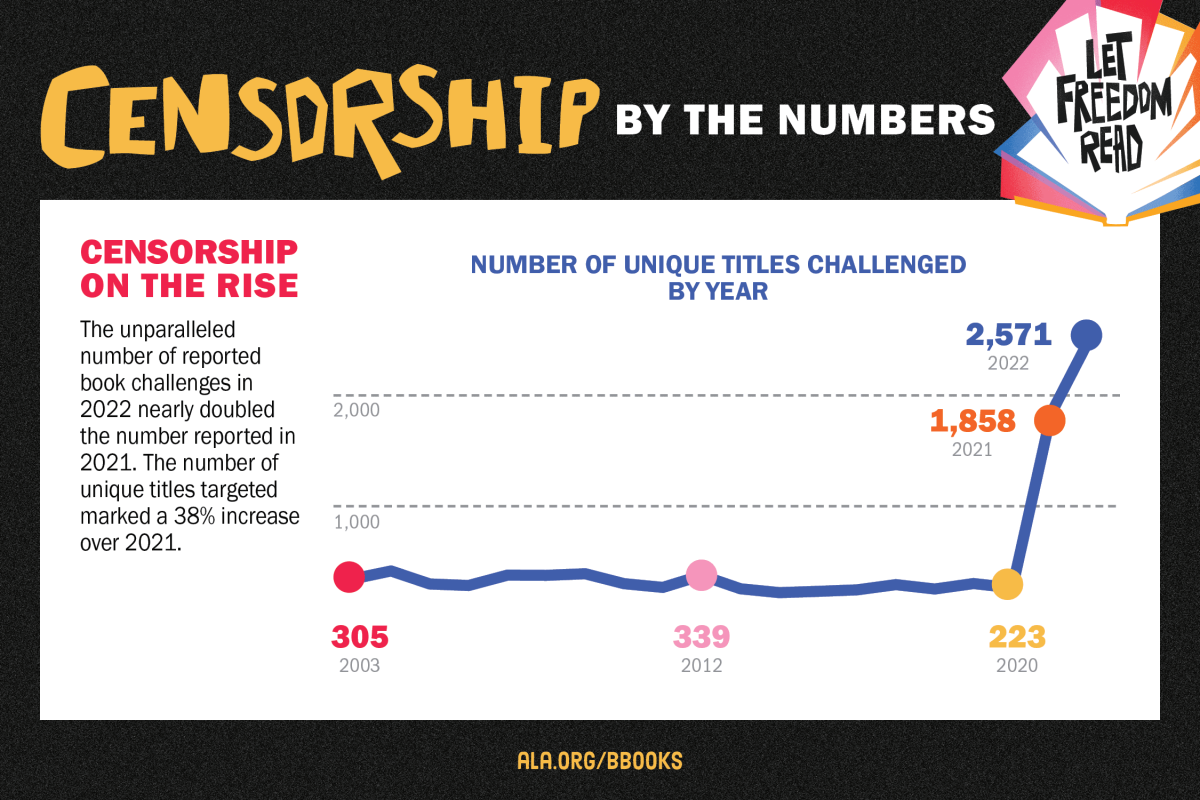

Now we’re seeing a truly unprecedented rise in book challenges to public, school, and university library materials and services.

In 2022, ALA documented 1,269 attempts to ban or restrict 2,571 unique titles.

Additionally, more than 90% of the attempts to restrict library resources in 2022 targeted multiple titles. Up until 2021, most challenges to library resources only sought to remove or restrict a single book.

So what’s changed?

THE WHO:

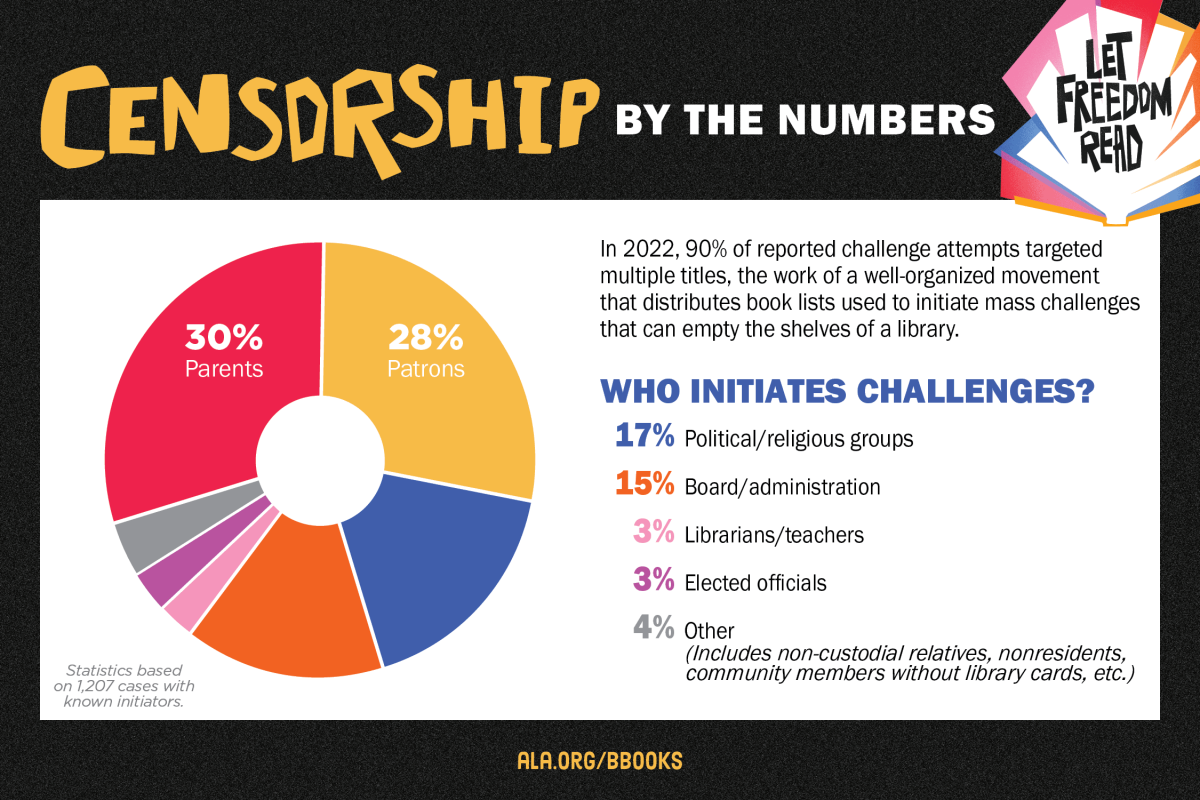

NOTE: These numbers could prove to be very interesting with more investigation, as it’s currently hard to say exactly how big the overlap between parents, patrons, political and religious groups, boards and administration, and elected officials really is given what we know about groups like Moms for Liberty.

According to PEN America, there are at least 50 organized groups, from local to national levels, pushing for book bans across the country. At least 8 of these groups have over 300 chapters or branches between them: Moms for Liberty (over 200), US Parents Involved in Education (50), MassResistance (16), Parents’ Rights in Education (12), Mary in the Library (9), County Citizens Defending Freedom USA (5), and Power2Parent (5). Of those chapters, over 70% were formed in 2021. (Fun fact: A lot of Moms for Liberty’s initial momentum rested in resistance to mask mandates in schools because of course it did.)

THE WHY:

Now comes the most interesting question: What is the point? The reasons typically given for all this tend to fall into two categories: a) “parents’ rights” to determine what their kids learn, read, and do and b) “protecting the children” from indoctrination, grooming, and emotional distress.

Let’s be real, here. While some of these folks may indeed be well-meaning citizens who are concerned with the mental, physical, and emotional safety of our nation’s youth, it becomes very clear very fast that most of them have other motivations–attention and money, for starters.

The main reason for these aggressive challenges, though, is to gain complete control over public access to information and education. If you control the narrative, you can keep children unexposed to ideas and experiences you don’t approve of. When you control the narrative, you can erase people and their stories from history and the public eye. You can isolate them, dehumanize them, and eventually get rid of them–one way or another.

When you control the narrative, you can say whatever you want.

The fewer stories there are (particularly healthy, positive stories) about queer people available, the more alone they feel, and the less likely they are to be open and honest about who they are. Additionally, it then becomes easier for other people to believe that queer people are so few and far between that their treatment is no cause for concern, that they must be doing something wrong to be treated that way, that they must have deserved it somehow.

This isn’t just true for queer folks, either. The other theme many of these challenged titles share is that they are often realistic portrayals of how the United States as a country treats people of color, particularly its Black citizens, from past to present. The picture isn’t pretty, but history usually isn’t when you look beyond the surface. Even the implication of the lingering damages of systemic racism in the US, let alone the thought that it may still be perpetuated even today, is enough to prompt banning attempts.

THE HOW:

How do they gain so much traction, though? Well, aside from the political support they start with, there’s a tried and tragically true method for turning diversity and inclusion into a hot-button issue here in America:

Step 1: Invalidate claims from the opposition by changing the conversation so that definitions are murky, but the connotations remain (see: the Christopher Rufo method).

Step 2: Take buzzwords (“grooming,” “gender ideology,” “critical race theory,” “propaganda,” “indoctrination”) and apply them both frequently and loudly.

Step 3: Rinse and repeat until you get results.

If this all sounds a little wacky, that’s because it is. But that doesn’t mean it’s not happening, and that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have serious consequences. These people are organized, coordinated, alarmingly aggressive, and, in the case of Moms for Liberty, financially backed by and affiliated with major right-wing organizations and Republican party leaders. They engage in fear-mongering and prey on parents who are exhausted, afraid, overworked, and overwhelmed with the world.

There’s also a pretty big overlap here between this particular movement and conspiracy theories about COVID-19 along with other anti-intellectual talking points that have been gaining traction over the last few years. An excerpt from PEN America’s “Banned in America: The Growing Movement to Censor Books in Schools” sums it up nicely:

“While parents and guardians ought to be partners with educators in their children’s education, and need channels for communicating with school administrators, teachers, and librarians, particularly concerning the education of their own children, public schools are by design supposed to rely on the expertise, ethics, and discretion of educational professionals to make decisions.

In too many places, today’s political rhetoric of “parents’ rights” is being weaponized to undermine, intimidate, and chill the practices of these professionals, with potentially profound impacts on how students learn and access ideas and information in schools.”

According to a lot of these folks, librarians are no longer relatively objective experts in their fields just trying to do their jobs but are instead elitist gatekeepers with An Agenda.

So where does that leave us?

WHAT NOW:

Well, according to the American Library Association, 2023 is on track for a 20% increase in book challenges. With elections on the horizon, it’s likely to get worse, with many conservative politicians promising to Protect America’s Children. It’s clearer than ever, though, that the only thing they’re interested in protecting is their own chances for election. To that end, they’ll throw whoever they need to under the bus, and who easier to do so with than children, who they can oppress and venerate all at the same time?

See, the thing is, it’s not just about a few books. It’s about representation, and how we all deserve to not only see ourselves in the media we consume but also windows into the lives of people with very different stories from our own. Those windows broaden our perspectives and help us develop empathy and, in some cases, they can help us understand things about ourselves we didn’t even realize we were missing. When queer kids don’t see themselves represented, and when all they hear is the vitriol directed toward people like them, they begin to feel confused, targeted, depressed, and isolated.

Does that sound like protection to you?

As a queer librarian, it’s also very isolating and depressing, and many of us are being directly targeted with harassment and potential violence. It’s disheartening, to say the least. Speaking only for myself here, it’s incredibly demoralizing to be accused of being a pedophile groomer because I want kids to have a positive representation of queer people available to them, either as a mirror or as a window.

You got me, y’all, I do have an agenda. It has a single item on it, and it’s “make queer kids slightly less likely to want to kill themselves.”

Sue me.

FINAL THOUGHTS:

The internet is a cesspool of nonsense, but it has also changed the game in terms of information exchange. Not all of that is good, necessarily, because we’re constantly inundated with information from all sides and it becomes difficult to parse what’s factual and what isn’t–which is kind of what groups like Moms for Liberty are counting on, to be honest–but it also becomes much more difficult to exert social control through isolation and curated information flow.

It’s harder to dehumanize queer people when it’s so much easier for us to find one another, and for others to see us and realize we’re, you know, people.

The truth is, this massive rise in book bans, anti-LGBTQ+ legislation, and trans panic is a product of fear—fear of change. Of progress.

Too bad. We’re not going anywhere.

They get loud when they know they’re losing.

Be louder.

Want to learn more? Follow Book Riot’s censorship tag for news and updates. To learn what you can do to help, check out Book Bans: A Guide for Community Response and Action from GLAAD and EveryLibrary, Get Ready, Stay Ready: A Community Action Toolkit, and A Template for Talking with School and Library Boards About Book Bans from Kelly Jensen.

Kayla Martin-Gant (she/her) is a queer, disabled librarian and lover of all things spooky. She wrote her first story, called The Haunted Dollhouse, when she was seven years old and received rave reviews from the playground crew. You can find her yelling about various and sundry things on Twitter and BlueSky @poultryofperil.