Celebrating Horror’s Past: The Others: How Trauma Rips The Family Apart and Brings Them Back Together

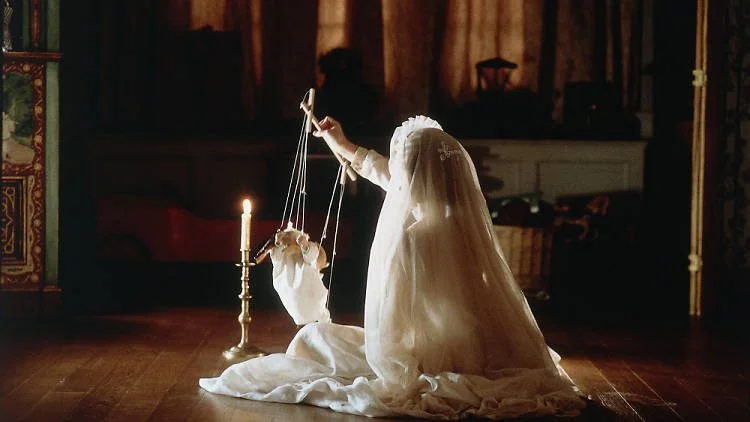

The Others (Amenábar, 2001) may appear at first glance to be a Gothic horror surrounding a young family in the Channel Islands, but upon analysis is a far richer text than first appears. Trauma surrounds this family at every turn, whether this be immediate personal trauma, historical trauma, or religious trauma, and while it initially fractures the family dynamic, it is accepting and living with the trauma that brings this family back together. In this essay I will discuss how The Others explores many types of trauma through the characters of Grace, Charles and Anne, and how the effects of trauma are explored throughout the film.

The film’s main protagonist is Grace, played by Nicole Kidman. Grace is characterised as stern and overly protective of her two children, Anne and Nicholas. She is overprotective by necessity as her children have a life-limiting disease and could potentially die if sunlight hits their skin. She is portrayed as being overly hard on her daughter Anne, who is rebelling against her mother and starting to exhibit strange behaviour. It is very easy to write Grace’s character off as overly cold and cruel to her children, who will never be able to experience a ‘normal’ life. However, I would argue that Grace’s mindset comes from trying to overcompensate for past and future traumas. This film is set after the end of World War II, and Grace brings the war up several times. She mentions how the island was Occupied, and also on a separate occasion mentions how she was able to keep the Nazis out of her house. Living in an Occupied area during a war almost definitely had an effect on her mentally, and Grace has developed a cold veneer in order to cope with it. She was able to protect her children from the Nazis, but is unable to save them from sunlight, Mother Nature, taking them from her. She is physically unable to save them, which is one of the reasons she breaks the way she does later in the film.

Grace is not the only traumatised parent Anne and Nicholas have. For most of the film, their father, Charles, is absent, only reappearing for a short period. For the beginning of the film, his absence is explained as him being lost in the war, but upon his return it is discovered that is he confused and shell shocked. He is shown as struggling to eat or leave his bed, although he is able to interact with the children off screen. Although Charles manages to return to the family, the trauma he has suffered since he had been away means he is unable to reconnect with the family, and he then disappears again. It is insinuated later, after the plot twist at the end, that Charles, having accepted his death in the war, has been able to move onto a new afterlife, however, he has to leave his wife and children behind, therefore becoming an absent parent again.

The house is incredibly important to emphasise what the family are going through. The house is isolated, and Grace mentions how, due to the children’s illness, they cannot leave so people such as the priest have to come to them. This leaves the family isolated, physically unable to leave the house and, in many instances, have to be locked away from each other. The house is surrounded by a thick fog that does not lift until the last few frames of the film, and Grace is unable to leave the property due to this. The one time she tries to leave the house she ends up finding Charles, who has been lost, and does not attempt to leave again. The house is also a site of past trauma – it is where Grace had to defend herself and her children from the Nazis, and it is where they died. However, it is not only a site of trauma for the family, but also others. The servants, Mrs Mills, Mr Tuttle and Lydia, died at the house and were buried there, and cannot leave, however, they have already accepted their trauma and are there almost as psychopomps to guide the family into acceptance. At the end of the film, Grace asserts that the house is her house, and it changes as a site for trauma to a place of safety for her, the servants and her children.

What really sparks the conflict of the film, however, is the home invasion trauma that the family face. Anne mentions a new friend named Victor roaming the house, and that she has been seeing an old lady asking her questions. It is only when the other family move in that they all start to experience the trauma fully. Later in the film, furniture is moved, noises are heard, doors are left unlocked, and the curtains are all taken down, leading Grace and the children to shelter for safety, for fear of the children’s death. They are not only retraumatised by what they perceive as home invaders causing a near death experience for Anne and Nicholas, but for Grace, it must seem as if the Occupation is happening again, reopening old wounds. During the film, this retraumatising becomes more evident. Grace becomes further and further traumatised and fearful throughout, which leads her to attack Anne as she sees the old woman instead of Anne. She is so fearful and unable to resolve her past traumas that she, unintentionally, scares her child. It is only at the end of the film, when the intruders leave, that Grace is finally able to resolve her feelings.

Anne is a source of frustration for Grace. She is at an age where she wants to explore and live, and Grace is forced to constrain her, due to trying to protect her from her potentially fatal disease. Anne acts out, refusing to obey/listen to Grace, and teases her brother by telling him about Victor and the old woman. While this initially appears just as a sister teasing her brother, it is more complicated than that. Anne also is the only one who remembers the initial trauma and references it multiple times. Anne states at different times that “she went mad like she did that day,” that “she wants to kill us,” and that “she won’t stop until she kills us.” That being said, while Anne remembers Grace attacking them, she does not remember dying and aggressively asserts that she’s not dead over and over during the séance. Anne is a subconscious reminder of the trauma which Grace struggles with, which leads to her disobedient behaviour, and Grace’s struggles with her.

It is not until the séance that Grace remembers what she has done. The dogpile of trauma that she experiences of her children’s illnesses, the war, her husband’s absence and her loneliness causes her to ‘go mad’ and she smothers the children then kills herself. But death is presented as a rebirth; she first hears laughter, which is a positive sound, and she is convinced that she had been given a second chance by God to be a better mother. Her interpretation could be seen to be true, as the film does not posit their deaths necessarily as a bad experience. It is due to their deaths that they are reunited with Charles. Charles was unable to find them until they die. It is implied they died weeks ago, and he says he was ‘out there, looking for my home’ for an extensive period of time. Their deaths allow them to reunite as a family for a period of time, and for Grace and Charles to confront each other. The film also doesn’t say that they will not be reunited again; when one of the children asks if they will see their father again, Grace simply replies with “I don’t know.”

The film also makes a point to show how death is freeing for the children. Not only is Anne shown dancing in the sunlight with no pain or fear, but there is laughter in that scene, and in our last shots of the house, the fog surrounding the house has lifted and the sunshine is able to fall down. The children are able to play in the sun and explore the grounds during the day with no fear of pain and death. In fact, this is the most unified we see the family throughout the entire film, so can this not be read as a happy ending?

In conclusion, while The Others initially appears to be a standard possession film, underneath the surface there is a story of a deeply hurt family attempting to come together and reconcile. Society considers death to be the worst trauma a person can face, however, it is only due to accepting their deaths that the family is finally able to be together and live a normal, happy life. This film also shows, through the character of Grace, how you may do horrific acts due to your trauma, but that you can make amends and recover from this as well. Amenábar shows throughout this text how recovery from trauma takes many forms, and how accepting trauma can improve life and relationships, even in untraditional ways.

Sarah R. New has been writing since she was 6. She specialises primarily in horror or fiction with horrific elements, but also writes speculative fiction and non-fiction. She has published three books: travel memoir The Great European Escape (2023), Gothic horror novella Amissis Liberis (2024) and literary body horror novella Hypochondria (2025). Sarah can be found on Bluesky, Instagram and Twitter under the username aldbera, or at sarahrnew.wordpress.com